Defence By Attack – Selkirk 1530 Most border towns did not have walls and so…

Selkirk Protocols Explained

The Herald of Scotland Explains the Selkirk Protocols

Parcels of history that were snatched from the flames: link

A nervous Government decreed in 1940 that combustible material had to be removed from commercial premises in case of attack — and that was when two more Selkirk brothers, Bruce and Walter Mason, spotted sweating workmen lugging half a ton of old paper out of the attic of the Border town’s branch of the long-vanished Commercial Bank. The Masons swiftly stepped in — saving the lode from precautionary incineration in the bank’s back yard.

The Keeper of Historical Records at the Scottish Record Office, described it as ”the most valuable collection of medieval documents to have come to light in this country”

The real importance of the find lies in the insight provided into the merry doings of Selkirk folk across 400 years. It’s often a grim story. In 1645, after the battle of Philipshaugh, town leaders deliberately shot to death captured camp followers from Montrose’s defeated army — most of them Irish women. One document suggests that local worthies donated powder and shot for the job, listing their names with apparent pride.

……………

IN the year 1591, James and John Ker of Selkirk had a little problem with their brother Thomas, a lawyer of the town. Thomas, it seems, was more than a mite fond of a drink. Being of a legalistic family, Thomas was enjoined into a binding contract — and given an offer he couldn’t refuse. Henceforth, Thomas agreed that”he sall at na tyme fra the day of the dait heirof to the feise and terme of Witsounday . . . drink in na places quhair he man pay money for.”

If some employer regaled the errant Ker as reward for a job, that was fine. If, however, Thomas backslid and actually paid for a drink, he would not only ”incur diffamation”, James would not give him, as pledged, ”ane pair of gray russit breikis he hes presentlie weirand” and John wouldn’t be parting with his ”quhit fusteane doublet”. Whether Thomas stayed out of Selkirk’s ale shops or not, we’ll simply never know.

This surreal tale — carefully noted down in arcane Scots in one of Selkirk’s earliest ”protocol books” — was bequeathed to history by an invasion and bombing scare 349 years later. A nervous Government decreed in 1940 that combustible material had to be removed from commercial premises in case of attack — and that was when two more Selkirk brothers, Bruce and Walter Mason, spotted sweating workmen lugging half a ton of old paper out of the attic of the Border town’s branch of the long-vanished Commercial Bank. The Masons swiftly stepped in — saving the lode from precautionary incineration in the bank’s back yard.

The rest is history. Earlier this year, Donald Galbraith, Keeper of Historical Records at the Scottish Record Office, described what the brothers Mason carried off that day as ”the most valuable collection of medieval documents to have come to light in this country within my experience”.

By any standards, Bruce and Walter Mason — known to the townspeople as a quiet, even retiring, duo who ran a small bakery — were remarkable men. Their father appears to have set up in business around the turn of the century in Paisley as a retailer of anarchist literature. The works of the saintly Peter Kropotkin being regarded as virtually dynamite in Edwardian Renfrewshire, it seems that Mason pere rapidly found himself

blacklisted.

From their youngest days in the Borders, the Mason brothers carefully collected local history. Local historian Walter Elliot was asked to help clean the attic after Bruce Mason’s death in 1963. ”He had masses of flints, Roman pottery and French glass.” Sadly, most of that collection was sold — though some did end up in the town’s museum. Just what was in the brown paper parcels tied up with string in Walter’s home, no-one had yet realised.

When Walter Mason died in 1988, Ettrick and Lauderdale district’s museum service found that they had inherited what curator Ian Brown describes as ”the third most important collection of municipal documents after those from Aberdeen and Edinburgh”.

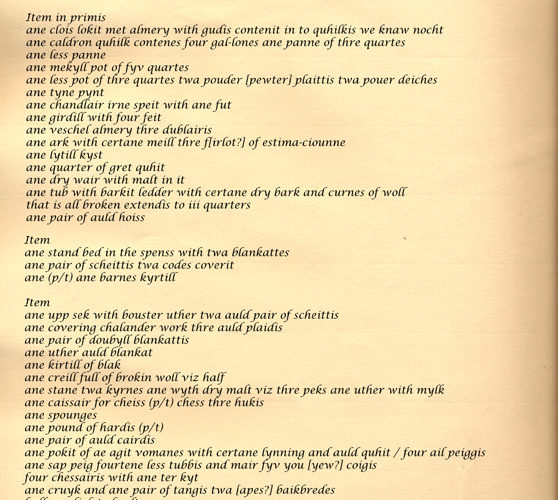

The surprises are still coming. One recently unwrapped parcel contained an 800-page protocol book (effectively a lawyer’s office records) covering the period between 1579 to 1587. All human life is there. In 1585, ”ye right Honorable Walter Scot of Branxholm and allegit that his deputies at his command has apprehendit John Wod son to Peter Wod in Jedburgh with ane naig of grey colour at auld Melrose which naig the said John has confessit as was allegit that he rest the same in Nenthorne beside Lambermuir frae John Greve.”

Transcribing and conserving protocol books alone will take perhaps four years. A new charity, the Walter Mason Trust, is urgently raising funds for the work. Lectures by Walter Mason Trust activists are already tearing droves of Borderers away from their television sets.

Walter Mason’s rescued parcels cover his adopted town’s life and work from the early 1500s up to the 1850s. Scholars will inevitably home in on the protocol books — revealing land-holding patterns and details of late medieval will provisions.

But perhaps the real importance of the find lies in the insight provided into the merry doings of Selkirk folk across 400 years. It’s often a grim story. In 1645, after the battle of Philipshaugh, town leaders deliberately shot to death captured camp followers from Montrose’s defeated army — most of them Irish women. One document suggests that local worthies donated powder and shot for the job, listing their names with apparent pride.

That anarchist bookseller from Paisley would surely have warmed to news of local dissent in 1798 — when ”Malicious and Evil-disposed Person or Persons, unknown, SET FIRE to one of the Factory Houses belonging to William Rodger.” Rural Scotland did not flock gently into

the Industrial Revolution’s dark satanic mills.

Borderers never did sit easily with state power. Selkirk’s procurator- fiscal, George Rodger, warned in 1806: ”Any person laying Lint, Dirt, Rubbish etc in the River or Streams, to forfeit Twenty Shillings Sterling.” His warning continues: ”And with respect to poaching, the Procurator-Fiscal expects that more attention will be paid to the Game Laws than has hitherto been done.”

He hoped in vain. During agitation over the 1832 Reform Act, rebellious citizens stoned local grandees in their carriages. Mr Rodger issued a poster offering #60 reward for apprehension of the rioters. There doesn’t seem to have been many takers. A few years earlier, one document records Mr Rodger on another probably futile hunt — promising ”Forty Guineas” for the name of the miscreant who fired a shotgun through the window of the Duke of Buccleuch’s gamekeeper.

Determined to quell agitation, one Ebenezer Armstrong volunteered for the militia in 1820, assuring his masters that he ”had no rupture, nor ever was troubled by fits”.

What Bruce and Walter Mason saved from the flames reveals all manner and condition of folk passing through a Scottish town. In 1855, locals were enjoined to keep a sharp lookout for two barefoot Irish girls. Sarah O’Donnell ”employed herself about houses — at any coarse work” and was wanted for ”theft from a hedge”. She had probably stolen firewood.

More exotic robbers seem to have headed for Selkirk too. In 1829, the town authorities were warned thus: ”Sir, I annexe a description of five persons, who are accused of lifting three Bodies, from the Church Yard of Lasswade in this County on the night of the 20th Ult, and have absconded.”

Ian Brown’s first priority is to raise an estimated #45,000 for immediate conservation of the Walter Mason documents up to 1700. Eventually, the protocol books will be published. The dream is to have a local study centre where future scholars and historians can fully recover the riches snatched from the flames in 1940. Meanwhile, still wrapped in paper and string, the bulk of the hoard is being carefully stored in the archives of Borders region library service.

In a recent radio interview, Walter Mason’s nephew spoke of locals believing that his uncle kept ”rubbish in the attic”. The shy baker’s rubbish is now attracting international excitement. Walter Mason had learned one anarchist lesson well — care and respect for the lives of others mattered more than money. What he left in his loft, it’s now clear, was beyond price. Scotland is the richer for his gentle dedication.

This article was written on 2 Jan 1990 in The Herald Link