Galloway description 1654 "The inhabitants engage in fishing both in the surrounding sea and in…

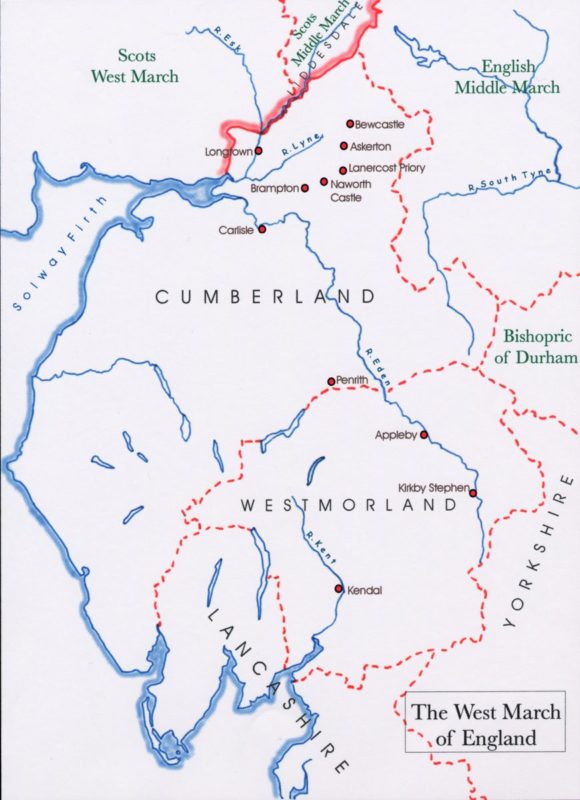

Cumberland West March England Maps 1580 – 1665

Cumberland 1622 map

Based on notes and sketches 1580-1613 by Timothy Pont who travelled in Scotland and northern England. Although robbed and suffering in primitive conditions, his notes, updated by Gordon of Straloch, were the basis of the first maps of Scotland created by Blaeu in the Netherlands who made an atlas which included maps based on the notes and sketches. The atlas has text that was translated into Latin and has been translated into modern English by the National Library of Scotland [NLS]. The maps have been digitised and made available online by NLS and Charting the Nation [CTN] and the user can zoom into the maps and see great detail. Some maps were copied into separate sheets and the reverse has text either in medieval French or Latin. On the reverse of some maps Timothy Pont states that because of war there was a danger in travelling to England, thus the origin of the information published on the reverse of the Cumberland and Northumberland maps is uncertain. The Cumberland map was published in Blaeu Atlas Maior 1662-5, Volume 5 Cvmbria, Vulgo Cumberland. The Roman Wall is clearlsy shown continuing to Bowness though the towers on the Wall are unlikely to be the pele towers that protected settlements from the Border Reiver raids. The tent on Sollome Moss may signify the location of the Battle of Sollome (Solway) Moss.

The map has been digitised by the National Library of Scotland website and can be zoomed with the scroll wheel of a mouse or click the +- on the map.

Cumberland 1662 Map : National Library of Scotland website

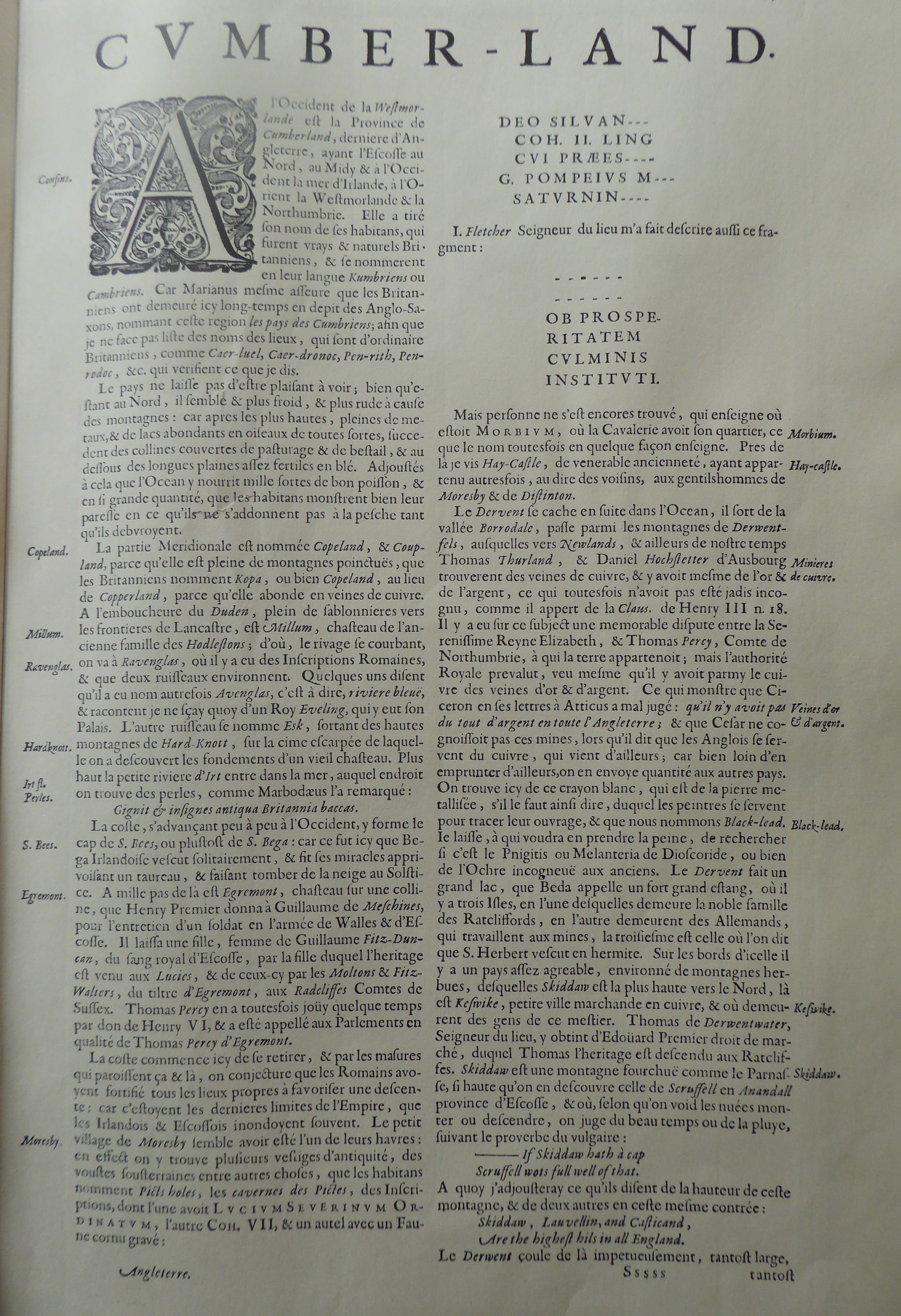

Description of Cumberland 1600 – 1654.

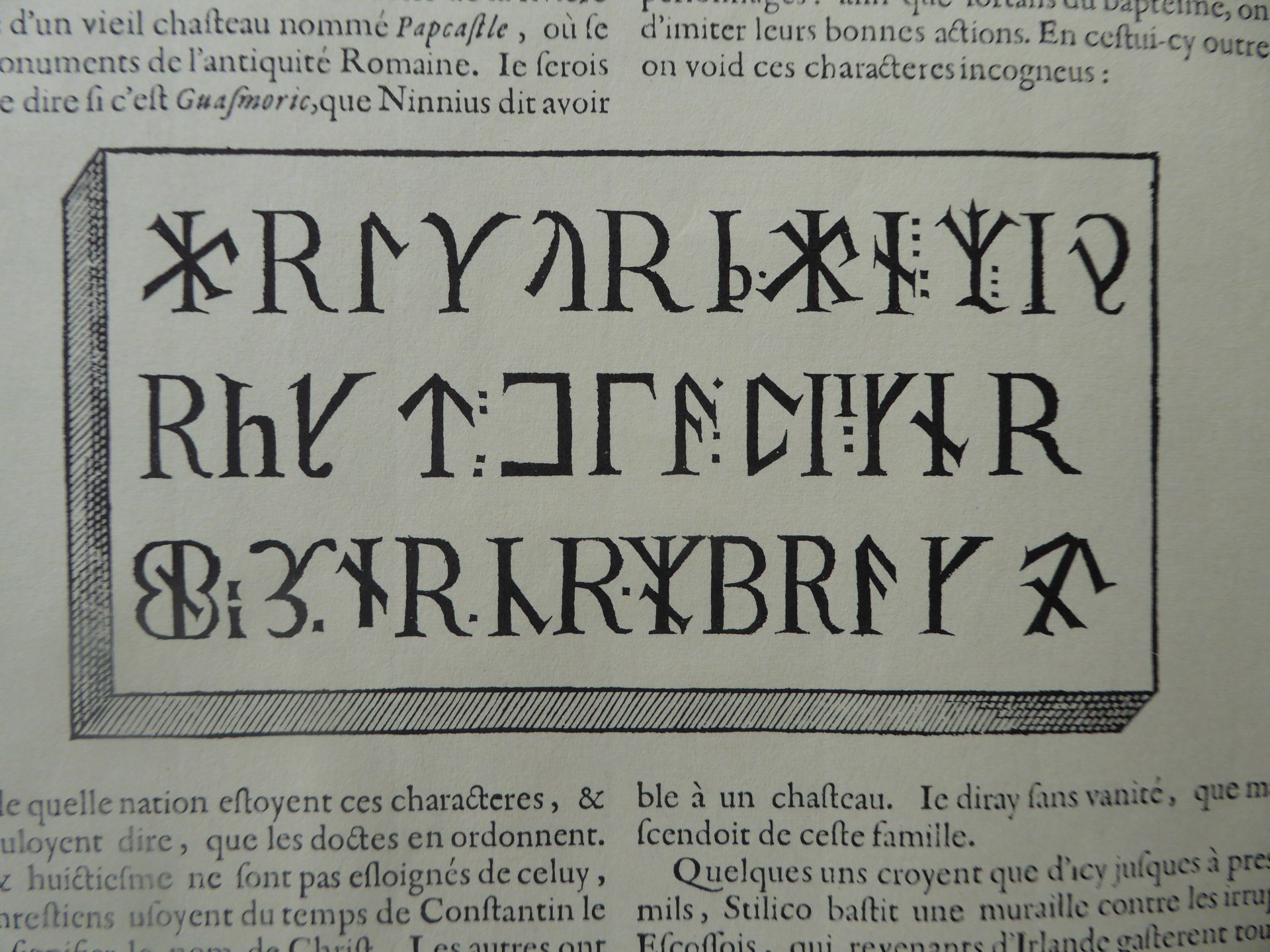

The National Library of Scotland website contains Blaeu Atlas of Scotland 1654 but this text is translated from the French on the reverse of a map and has not been translated by NLS, however it is likely to be based on text from Timothy Pont and Robert Gordon and from Camden: Britannia 1607 This translation is from medieval French on the reverse of my map.

The West of Westmorlande is the province of Cumberland, last of England, with Scotland at the North, at the centre and the West the Irish Sea, and at the East the Westmorlande and the Northumbrie. Its name has originated from its inhabitants, which were the real and natural Britanniens, and named themselves in their own language Kumbriens or Cambriens. Because Marianus is convinced that the Britanniens have lived here long enough despite the presence of the Anglo Saxons, naming this region the country of the Cumbriens; …….

The country is very pleasant to look at, even though it is in the North, and it is colder and harder because of the mountains: because following the highest, full of metals and lots of lakes filled with birds of all kinds, followed by little hills covered with meadows and animals and below are big plains, very fertile with wheat. Added to that the ocean feeds one thousand kinds of good fish in such a big quantity that the inhabitants show their laziness in the fact that they don’t fish as much as they should. The Southern part is called Copeland and Coupland, because it is full of spiky mountains which the Britanniens named Kopa, or Copeland, instead of Copperland, because it is abundant in copper veins. At the mouth of the Duden, filled with sablonnieres towards the frontiers of Lancastre, and Millum, castle of the ancient family of the Hodlestons; where the shore curves in we get to Ravenglas, where there have been Roman inscriptions and which is surrounded by two streams. Some people say that in the past it has been called Avenglas, meaning blue river and they mention a king called Eveling which I I have never heard of, who has had a palace there. The other stream is called the Esk, leaving the high mountains from Hard-Knott, a steep peak at the bottom of which was discovered the foundation of an old castle. Higher up, the little river Irt enters the ocean at which place we find pearls, as Marbodaeus noticed: “Gignit & infignes antiqua Britannia baccas.”

The coast, moving slowly towards the West, forms the cape of St Bees, or rather of St Bega: because it is here that Bega of Ireland lived as a hermit, and made his miracles of taming a wild bull, and making some snow fall at the solstice. A thousand paces from there is Egremont, castle on a hill, that Henry I gave to Guillaume de Meschines, because he gave support for a soldier in the army of Scotland and Wales. He left a young girl, wife of Guillaume Fitz-Duncan, of the Scottish royal blood, and through the young girl of which the inheritance came to the Lucies, and to them from the Moltons & Fitz-Walters, of the title Egremont, to the Radcliffes Count of Sussex. However, Thomas Percy enjoyed it for a little from Henry VI and was iven the title of Thomas Percy d’Egremont by Parliament.

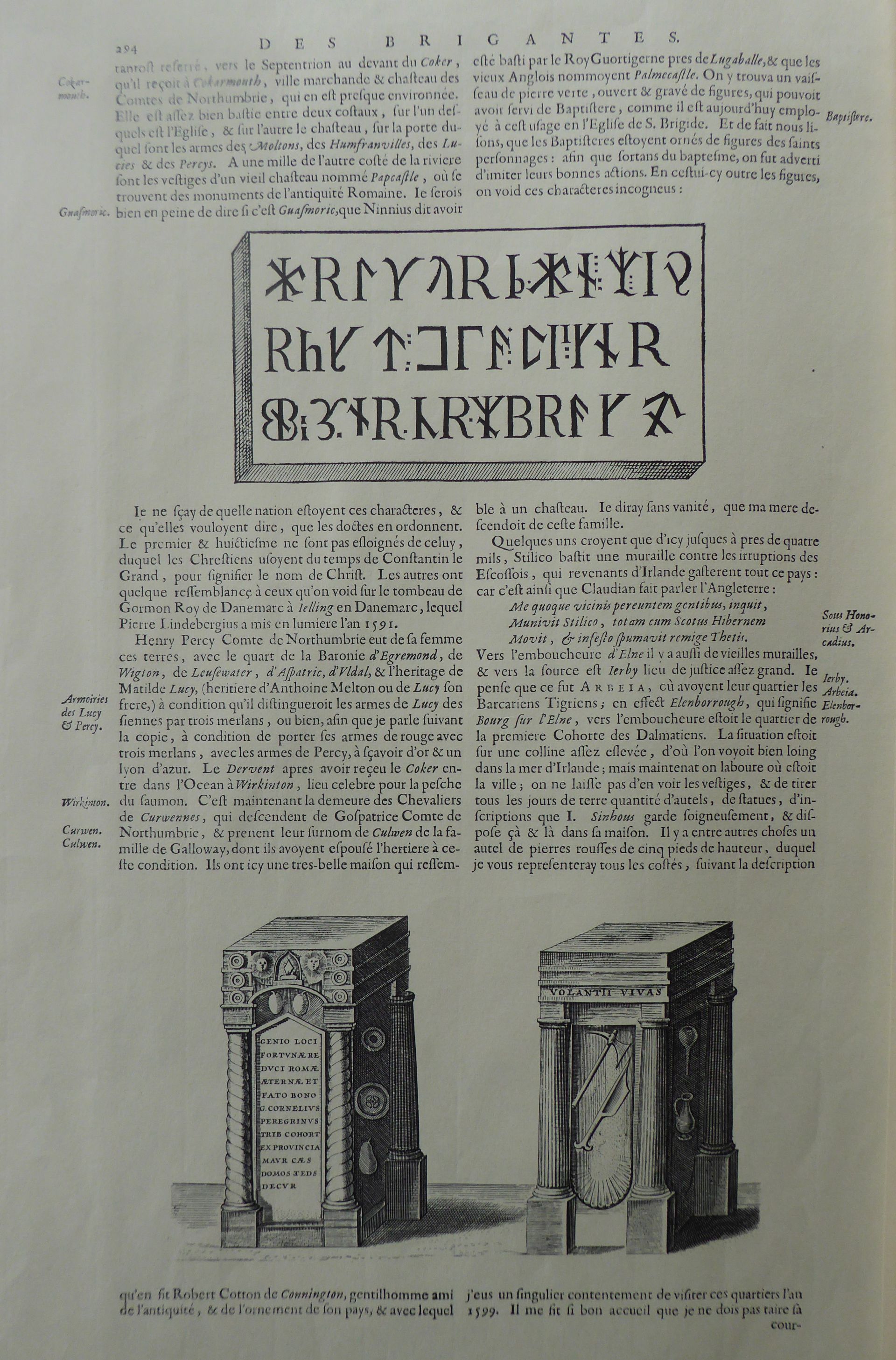

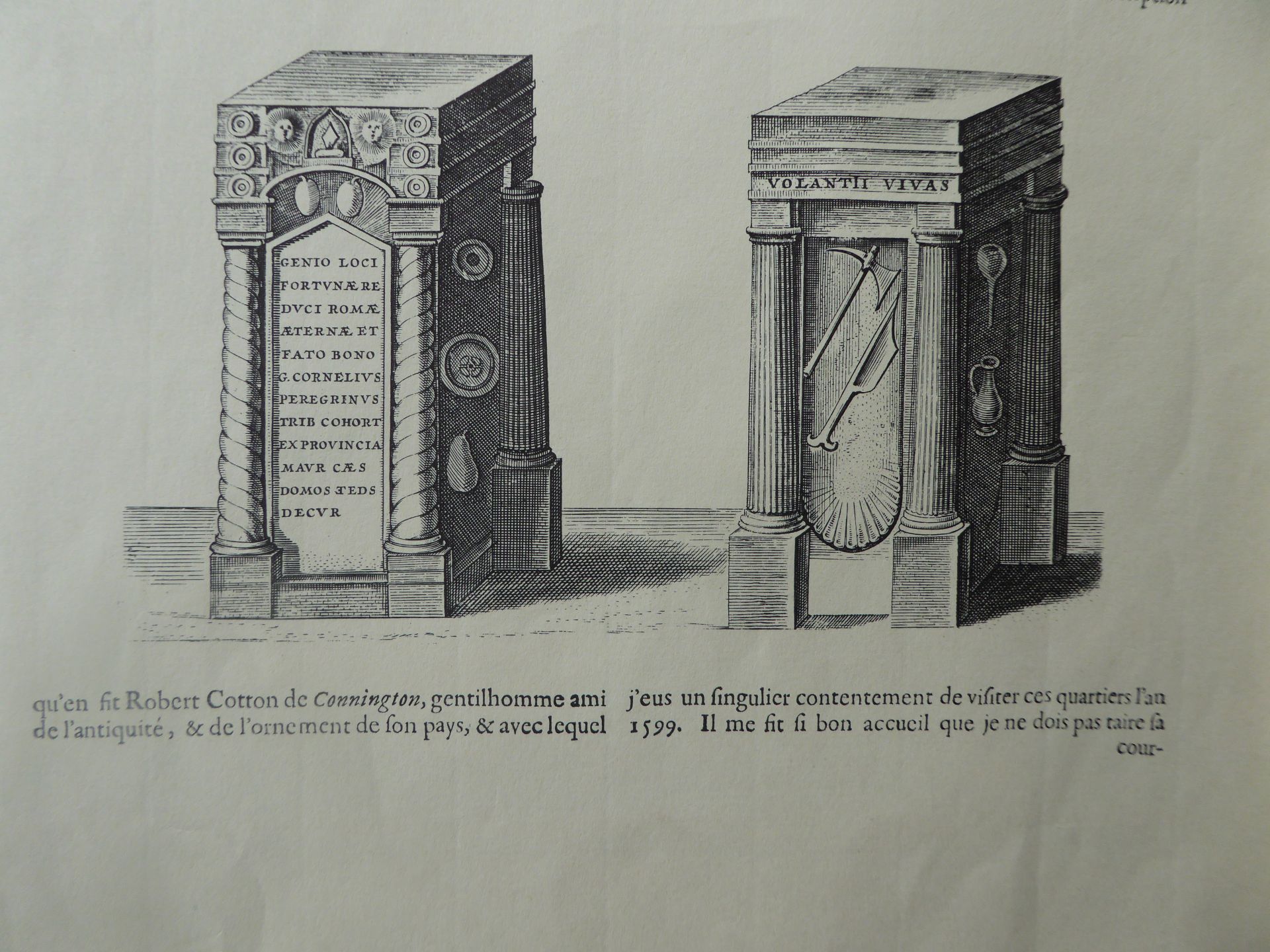

The coast starts to retreat here. We think that the Romans had some fortifications here because it was the last limits of the Empire that the Irish and Scottish reached. The little village of Moresby seems to have been one of their havens: effectively we can find many remains, amongst other things, underground vaults, which the inhabitants named picts holes, the caverns of Pictes, there are some inscriptions, one of which has “Lucium Severinum Ordinatum, the other COH, VII and an alter with a horned animal enscribed ……

Missed para

The Dervent then looses itself in the ocean, it comes out of the Borrodale valley, passes through the Derwent mountains, which is near Newlands, and elsewhere in this time Thomas Thurland and Daniel Hoschstetter of Ausbourg found copper veins and there was also gold and silver, however in the past it was not unknown, as it appears from the laws of Henry III n18. There has been on this subject a memorable dispute between Queen Elizabeth and Thomas Percy, Count of Northumbrie, who owned the land. Percy would not admit that there was gold or silver, but the Royal authority prevailed. This shows that in Roman times, letters claiming that there is no gold in England were untrue.

Translation of part of French text

We think that the Romans had some fortifications here because it was the last limits of the Empire that the Irish and Scottish reached. The little village of Moresby seems to have been one of their havens: effectively we can find many remains, amongst other things, underground vaults, which the inhabitants named picts holes, the caverns of Pictes, there are some inscriptions … Ausbourg found copper veins and there was also gold and silver.

English Scottish Border Maps 1580 – 1654 from Pont the traveller, Gordon updating & Blaeu the map maker

Around 1583-1596 Timothy Pont, a young graduate of St Andrews University, undertook his remarkable task of mapping Scotland – the first person to do so in any detail, as far as we know. Pont travelled around Scotland and the northern part of England making manuscript notes and sketches of the landscape and settlements. These were revised and added to by Robert Gordon of Straloch (1580 – 1661), and his son James Gordon, parson of Rothiemay (1615 -1686) and john Scot of Scotstarvet [Meikle 2003 p465]. The revised work consisting of three general maps of Scotland, 46 maps of Scottish counties or regions, and six maps of Ireland were subsequently published in 1654 by Joannis Blaeu of Amsterdam as Volume V of his Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, sive Atlas Novus. Maps of what is now Northumberland and Cumbria were made with interesting text on the reverse that describes the region at that time.

77 manuscript maps attributed to Pont have survived. Various editions and re-engravings were made but they are all based on observations made before Scotland and England united. Some editions of the maps have text on the reverse in Dutch, Latin, French or German which is assumed to be based on the observations of Pont updated by Gordon. Partial and approximate translations are offered in this resource and the National Library of Scotland also have translations, see links on this resource.

Travel in Scotland was not only arduous and difficult, but also dangerous. Scotland suffered bubonic plague in 1584 -1585 and 1586 and 1588. In the preface to Blaeu’s Atlas Robert Gordon says of Timothy Pont:

“He travelled afoot over the whole kingdom, which no person before him had done. He visited all the islands, inhabited for the most part by a barbarous and uncivilized people with a language different from ours and where he was often despoiled by cruel robbers – as I have heard him relate – and suffered all the hardships of a difficult and dangerous journey without growing weary or ever losing his courage”

For more information about Timothy Pont and 1645 maps of the border region see the National Library of Scotland links below.

The Scottish People 1490-1625 pages 464+ by Meikle 2003 Google Books online explains the difficulties surrounding the map making.

National Library of Scotland

The collection of Pont manuscript maps in the National Library of Scotland is one of the finest surviving collections of its kind. It has the research potential for a unique insight into the history, geography, landscape and architecture of 16th century Scotland. See https://maps.nls.uk/index.html

There is a nationally funded project to interpret the Pont manuscripts and the maps that were produced as a result of the manuscripts. This Project Pont is co-ordinated by the National Library of Scotland www.nls.uk If you would like to know more, want to subscribe to the newsletter, or can contribute then email maps@nls.uk

Search for The Border Reivers on modern Ordnance Survey map

A remarkable undertaking by Stuart Hepburn of Carlisle has identified hundreds of sites that are relevant to the Border Reivers. The reverse of the maps contains a short description, the type of site, the OS grid reference and the grid location of the site on the other side of the map. It is an excellent resource for anyone seeking to travel in the borders “in search of the Border Reivers”

If you search for the remains of sites indicated on the Blaeu maps based on Pont and Gordon’s notes in 1580 – 1640 then please realise that private property must be respected in any exploration, and realise that the surveyors and cartographers sometimes were wrong. For example some rivers and hills are marked as settlements and some valleys are 90 degrees out of alignment. See Dumfries in Nithsdale for an example that indicates the difficulties that Blaeu based in Holland in 1640 had when interpreting the notes and sketches made by Pont in 1580 – 1605(?)

Contact this site if you would like a copy of the map which is no longer retailed by Ordnance Survey.

Purchase re-printed Pont Blaeu Maps of 1665

The maps in the this project were kindly supplied by

Paul Clark – The Carson Clark Gallery, Scotland’s Map Heritage Centre

181-183 Canongate, Royal Mile, Edinburgh EH8 8BN

scotmap @ aol.com

The maps are printed on high quality paper 65 x 55 cm and help us to appreciate what was known of the topography and settlements of the borders in the period 1590 – 1665.

The following are a list of maps available from Carson Clark Gallery: http://www.carsonclarkgallery.co.uk/

Scottish / English Borders:

S01 TEVIOTDALE (TEVIOTIA) – Roxburgh

S07 ESKDALE (EVIA ET ESCIA) – N.E. Dumfriesshire

S08 LOWER ANNANDALE (ANNANDIAE) – S.W. Dumfriesshire

Cumberland (CVMBRIA)

S02 UPPER TWEEDSDALE (TVEDJA) – Peebleshire & Selkirkshire

S06 LIDDESDALE (LIDALIA) – South Roxburghshire

S04 BERWICKSHIRE (MERCIA)

S09 NITHSDALE (NITHIA) – West Dumfriesshire & small parts of East Kircudbright & Ayrshire

Northumberland (NORTHVMBRIA) Blaeu

Text on the reverse of the Blaeu maps from Pont / Gordon

On the reverse of the maps some text has been printed in medieval French which seems to be based on the observations of Pont / the Gordons. We have translated part of this text but this is an interpretation and not an academic translation. If you can translate the text please email your version to this site.

There is a larger project Charting the Nation http://www.chartingthenation.lib.ed.ac.uk/ which aims at “Preserving and Widening Access to Maps of Scotland and Associated Archives 1590-1740

The Charting the Nation image collection includes a wide variety of single maps and maps in atlases and other bound books, together with important manuscript and printed texts relating to the geography and mapping of Scotland from 1550 to 1740 and beyond.

The site contains invaluable source materials for the study of the history of cartography, architectural history, genealogy, military history, environmental history and archaeology, amongst many other disciplines. Over 3,500 high resolution images are currently available.